Entry #3: Mile 1, Boston Gate. Transitions

Transitions

It is often difficult to imagine what a place must have been like in a different time. Even in a town as steeped in history as Boston, it can be difficult to envision the lay of the land in the seventeenth or eighteenth century. Most of the buildings have long since disappeared or been destroyed by one of the many fires that have devastated the city since its founding in 1630. The roads have changed too, but less than one might imagine. The original road out of town down to the Neck still exists, although it has been completely transformed by development of almost four centuries. I aim to walk to the original entrance to the town of Boston, the gate on Boston Neck, which was first built in 1631. This gate is only a little more than a mile from where I stand in front of the Old State House, but this is one of the most historically dense miles in all of the United States. I aim to walk back and forth in time as well, attempting to recall what was and to examine what is. The gate is long gone, much of the area formerly under water has been reclaimed by landfill, the inhabitants have changed dramatically over time, both in number and in provenance, but the road still exists and there are many stones that still speak of another time.

*****

In 1690, after seventy or so years of British colonization of North America, five settlements in the American colonies could be considered to be more than villages: Boston, Newport, New York, Philadelphia, and Charles Town (Charleston, South Carolina)(1). Together these five provincial towns totaled about ten percent of the entire population of the colonies, which has been estimated at about 206,000 (2). Boston, with roughly 7,000 people, was by far the largest town in the American colonies, followed by Philadelphia and New York each with about 4,000, Newport with approximately 2,600, and Charles Town at the foot of the table with 1,100 inhabitants. Boston would remain the largest town in Colonial America until the eve of the American Revolution, and the three largest aforementioned cities would maintain their lead as the largest cities for over a century. In between these five settlements “stretched eleven hundred miles of wilderness, broken only by rare and occasional settlements.”(3) The road connecting these cities would have been a lonely and dangerous place, through territories still not under the control of the Englishmen who nominally ruled the colonies and peopled by understandably hostile Pequots, Narragansett, Massachusett, and other Indian peoples, through dark and dangerous woods populated by bear, catamounts, rattlesnakes, and wolves, intersected by fast running and wide rivers, and bereft of decent places to sleep or eat. A trip on the road that would become known as the Post Road was an adventurous journey, not to be taken lightly.

*****

The position of Boston on the Shawmut peninsula was not an accident. Surrounded on all sides by water save for the Neck connecting it to the mainland, it was relatively safe from assault by hostile native people, and its position well inside a large and almost landlocked harbor kept hostile forces from across the sea at bay. By 1740, Boston had more than doubled in size to about 17,000 people, all contained within the confines of the Shawmut peninsula. Although this seems small, it should be noted that only London (population about 675,000 in 1750) and four or five other towns in England (Bristol at 45,000 was the second largest town in England in 1750), exceeded Boston in population in the middle of the eighteenth century (4). Boston was still the largest town in the colonies, but the other towns were catching up and at the first census in 1790, New York (33,131) had become the largest town in the United States of America, a position it has maintained to the present time. Boston,with a population of 18,320, followed Philadelphia (28,522) as the third largest city in the new nation, but was only slightly larger than it had been fifty years earlier(5). The peninsula was quickly becoming full, and only the addition of more territory would enable the city to grow. Unlike New York or Philadelphia, the town was hemmed in by water and in order to increase in population would need literally to increase in land.

*****

When looked at from the perspective of an eighteenth-century visitor, Boston was a major metropolis, crowded and bustling, the seat of government and commerce, and a major destination for traders, settlers, and soldiers alike. One in thirty settlers in all of the colonies resided in Boston in 1690. Yet from the Old State House to the Gate which marked the limits of the town, the “street leading to the Neck” measured a mere one mile and a few yards. This thoroughfare was and continues to be, the main commercial road in Boston. Today the city limits of Boston are much greater and the population of the city proper is close to 600,000.

On this day it continues to be a crowded and bustling metropolis. In addition to the normal ebb and flow of weekday workers in downtown Boston, the city is filled with the limping sneaker-wearers leftover from the 114th running of the Boston Marathon, a Patriot’s Day tradition. A holiday in Massachusetts in remembrance of the Battles of Lexington and Concord, Patriot’s Day is a fitting time to reflect on the Post Road as it played an extremely important role in the events of the day. But I will save William Dawes and his heroic but less celebrated ride down the Neck to Lexington for a future entry.

The site I am standing on, the spot that marks the beginning of the Post Road, is also a site of great renown in American history, the site of the famous Boston Massacre of March 5, 1770, the place blood was first spilled over the events which led to the independence of the United States of America. The image of that day was memorably recorded on an engraved print produced and distributed by Paul Revere, in which some liberties were taken with the facts in order to arouse the ire of colonists everywhere. Here the grinning redcoats are wantonly firing into a crowd of innocent bystanders beneath the ironic sign of the nonexistent Butcher’s Hall. The reality, as recorded during the trial of the soldiers in the Town House (Old State House), was somewhat murkier. Although five people were killed by soldiers, it appears that a simple dispute over an unpaid bill escalated into an angry mob of young men (without the elderly widows shown in the engraving) confronting a lone soldier in front of the Royal Custom House. When a rescue party of eight soldiers arrived to extricate the guard from this dangerous situation, the mob began hurling epithets, rocks, snowballs and other projectiles at the soldiers. One object struck a soldier in the head and knocked him down and events quickly took a turn for the worse. Shots rang out, the crowd scattered, the commanding officer quickly ordered the firing to cease, and dead and dying bodies were strewn on the ground. Most of the dead were working class people in apprentice positions and included Crispus Attucks, who was black, and Patrick Carr, who was Irish. The events were quickly utilized by Samuel Adams and others to fan the flames of passion against the tyrannical actions of the Crown as represented by the soldiers. However John Adams, Samuel Adams’ cousin, the first vice president and second president of the United States, and a major figure in the events leading to independence, defended the soldiers and all but two were acquitted; these two were branded on the thumb and freed. It appears that propaganda was used as liberally and effectively in the media as it is today.

The Boston Massacre as seen on Fox News.

The Old State House itself was also the scene of many important events in the eighteenth century. As the seat of the the court, the town government, and the Provincial government represented by the Royal Governor and appointed officials as well as the elected General Assembly, it was bound to be the scene of many of the important debates over governance that ultimately led to the reading of the Declaration of Independence in Boston for the first time from the balcony of the building in July 1776. After independence, the building itself quickly was replaced by a larger and grander edifice on Beacon Hill which is still in use as the seat of state government. The building fell into disuse and almost ended up in Chicago, until local interest and pride were awakened, and the building was preserved as a museum run by the Bostonian Society.

*****

As soon as I embark on my first few steps on the Post Road I am accosted vigorously by a drunk who wants a dollar for “bus fare.” He seems always to need bus fare, always to be in the same place, and always drunk. A few more steps leads me past a taxi driver and a pedestrian engaged in a shouting match in which not a few profanities are vocalized loudly. Alexander Hamilton, a doctor from Annapolis who traveled the Post Road in 1744, was quite favorably impressed by the “politeness and humanity” of Bostonians. I am certainly seeing the human side of the humanity, but the politeness is in short supply as I embark on my walk. John Winthrop, one of the principal founders of Boston, who famously desired of the city and its inhabitants that it act as a model for all to copy-- “we shall be as a city upon a hill, the eyes of all people upon us”-- would be singularly unimpressed by the general comportment of many of the people on Washington Street today.

Just off Washington Street a few steps down from the Old State House is a small alley called Spring Lane, named for the water source which first attracted the Puritans to set up home in Boston instead of Charlestown across the harbor. At the corner of Milk and Washington stands the Old South Meeting House, built in 1729 as a Puritan meetinghouse but most famous as the meeting place of 5,000 colonists which led to the Boston Tea Party on December 16, 1773 (6). As the largest gathering place in Boston, this building, which replaced an earlier wooden structure from 1669, the Old South Meeting House served as a place of worship as well as a meeting hall. On the day after the Boston Massacre Samuel Adams held a massive protest meeting in Old South, and meetings were frequently held here when Faneuil Hall proved to be too small to accommodate the crowd.

Left: Spring Lane Plaque Right: Old South Meeting House

After the passage of the Tea Act in 1773, which effectively continued the policies of the Townshend acts by maintaining a tax on tea to defray losses suffered by the East India Company in part owing to illegally smuggled and cheaper Dutch tea, many in the colonies objected to what they perceived as the imposition of a tax upon them without any input from the colonies themselves, “taxation without representation.” As with the Boston Massacre, there were many other reasons for the anger at the government, and events have been portrayed in a somewhat more favorable light to than may have been warranted, but the Boston Tea Party, in which the men at the meeting house (some “disguised” as Indians) marched down to the harbor and dumped 342 chests of consignment tea into Boston Harbor to protest the Tea Act, marked a major turning point in the fight over governance of the colonies. The resulting closure of the port of Boston and loss of trade as a result only further inflamed many people in Boston, culminating sixteen months later in the clash at Lexington and Concord, the “shot heard round the world.”

During the occupation of Boston, Old South Meeting House was vandalized and desecrated by the occupying troops, who burned pews as kindling, and used the ground floor for equestrian sports. In March of 1776, British forces evacuated the town and General George Washington, commander of the Continental Army entered Boston through the Gate, marching up the road from the Neck, which was renamed in his honor in 1789 when he visited as President Washington.

*****

On the corner of School and Washington sits the building known as the Old Corner Book Store, built around 1720 on the site of an earlier house that was the home of Anne Hutchinson, who was famously expelled from Boston for her religious views in 1638, but most famous as the offices of Ticknor and Fields, publishers of many of the literary lights of the nineteenth-century “flowering of the New England mind”: Thoreau, Emerson, Hawthorne, Longfellow, Stowe, Twain, Whittier, and many others (7). The Atlantic Monthly was also originally published by Ticknor and Fields, as were many European authors, including Dickens, who was a great friend of James Ticknor and his wife, Annie. Boston in the mid-nineteenth century was the intellectual and literary capital of America, and this building was the “hub of the Hub” as Boston is known.

*****

Layer upon layer of history, of change, of people and buildings come and gone, one replacing the other replacing the other. Perhaps a rudimentary summer enclosure for a family of Massachusetts Indians once stood on the spot where the house of Anne Hutchinson stood, where the Old Corner Book Store stands now. Other more modern buildings stand where once other buildings both humble and of great importance stood. A plaque nearby tells us that the Province House, the former home of the royal governors of Massachusetts, once stood nearby. A map from 1769 shows house after house and many churches, taverns, and other commercial establishments leading from the Old State House, down what was called Cornhill to Old South Meeting House, becoming Marlborough to West Street, then changing to Newbury until Frogg Lane (now Boylston Street). The houses thin out after that on the section called Orange Street, the last half mile to the Gate, as the town slowly gives way to cultivated lands and the ever-encroaching water that engulfs the Neck frequently during high tides and storm surges. Almost every single structure on the map of 1769 is gone. The problem with doing a walk in a city as dense with stories as Boston is that the walk could take forever, and I might never leave the confines of the old town. I must curb my enthusiasm for recording every event and structure of note in order to make progress. Maybe I am afraid of letting go. Maybe I like the safety and comfort of the familiar streets of my hometown.

My entry grows longer and I have walked a mere 800 yards. I must move on. I will come back at a later date to revisit some of this treasure trove of stories. Onward to the Gate.

*****

As I continue down Washington Street I pass a small park where many office workers sit in the sunshine of early spring to eat lunch. Interspersed among the benches are overwrought statues of ragged starving men, women, and children. This is the recently created Irish Famine Memorial, and the irony is not lost upon me as I walk onwards. Along with college kids, groups of young girls all on their cell phones presumably texting each other, construction workers, street vendors, homeless people, elderly Asian women weighted down with numerous little red plastic bags full of groceries, I pass the hole where Filene’s once stood and worry about the future of the Downtown Crossing shopping district. It has a distinctly shabby feeling these days with many empty storefronts and a giant cavernous pit. There is still hustle and bustle but far less than thirty years previously when I took my girlfriend, now wife, on our first big date to the Mug and Muffin, a visit to Strawberries Record store and to Filene’s and Barnes and Noble (all gone). Ironically the area to the south has markedly improved since that time. Derelict theaters such as the Paramount and the beautiful old Opera House have been restored, the Ritz Carlton built a large complex a little beyond, and new buildings and hotels are popping up all the time in the area I knew as a kid as the Combat Zone, a very seedy red light district with porn shops, strip clubs, prostitutes, drug dealers, and not a few drug-addled individuals wandering down the street, perhaps thinking they were wandering around in the seventeenth and eighteenth century as I am purporting to do. There are still some of these folks, as old habits die hard, but the success of the Chinese-American community that coexists in this milieu and has done so for a century and a half, in pressuring the city to improve the area has been rewarded. Ironically, the vibrant Chinatown that attracts so many is slowly also being consumed by the encroaching development.

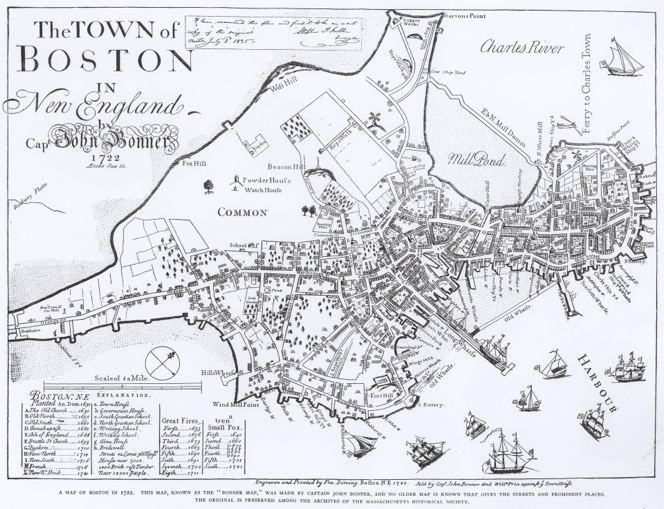

Bonner Map, 1722. Notice the paucity of buildings as the road heads out onto the Neck

Essex Street and Beech Street, the heart of Chinatown, are the last streets radiating off the road to the Neck on the 1722 Bonner map of Boston. Thereafter there are only a few dozen more houses, some cultivated land to right of the main road, and a few wharves fronting the South Cove to the left of the road. The land slowly narrows as I approach the fortifications that seal the town from the outside world. The map by William Price of 1769 shows in the intervening forty-seven years the addition of half a dozen new streets in the final half mile before the Gate, starting with Kneeland Street, which today signals the end of Chinatown. Today the other side of Kneeland is increasingly filled with hospital related complexes at the expense of the former New York Street neighborhood, once made up of small buildings filled with newly arrived immigrants. The South Cove area east of Washington Street was one of the first areas reclaimed from the sea using as fill gravel shipped in from Roxbury and Dorchester. By 1839, 55 new acres of land and three miles of new streets had been added to the growing town from the South Cove development alone. Additionally, a railroad terminus was established which still exists in today’s South Station (8). The addition of land on all sides of the peninsula by “tearing down hills to fill the bays” resulted in a dramatic increase in the geographical territory and the population of Boston. In 1800 the town of Boston contained 24, 937 people (9). By 1850, the now City of Boston, with expanded new neighborhoods in the South End, Back Bay, and South Boston, as well as the South Cove and other “smaller” landfill projects, contained 136,881 inhabitants according to the United States Census, a more than five-fold increase in fifty years (10). Many of these new residents crowded into the cramped housing of the areas around the South Cove and the South End, the area formerly known as the Neck.

*****

A block past the hospitals brings me to a more open and forlorn area around Herald Street (formerly Castle Street). Here Washington Street crosses the Massachusetts Turnpike and the aforementioned railroad tracks. In earlier times the South Congregational Church stood at this corner from 1828 until it was incorporated into the Columbia Theater in 1891 (11). The area is one of those areas “redeveloped” by the city during the craze for bashing down old “rundown” neighborhoods and throwing up newer buildings, in an effort to improve the outlook for these areas. It has not worked to great effect here. Ironically it does reinforce my sense of leaving the city and entering what was once the wasteland of the Neck. The Boston Redevelopment Authority in 1958 demolished virtually every building from Herald to East Berkeley and from Washington Street to the Fort Point Channel. Thus the area has a sense of desolation that might have been felt by a person traveling the Neck in 1640 or 1750.

One block later, I reach the intersection of Berkeley and Washington Street which marks the approximate location of the Boston Gate. A gate existed here as early as 1631, and the fortifications were continually enlarged and improved until the pressure began to build from the inside and the fortifications were demolished to make way for the incipient landfill and development that has characterized Boston’s growth ever since. Today this area, the beginning of the South End neighborhood, is undergoing a renaissance in sharp contrast to the area I have just passed through. Perhaps this is yet another transitional period in the history of this area, but it seems as though the highways, train tracks, lack of housing, and large number of parking structures and empty lots will mark a boundary between Downtown Boston and the neighborhoods to the south just as surely as the Neck and its fortifications did for almost two hundred years. I leave the familiar confines of the old town of Boston guided by Saint Botolph, the patron saint of travelers for whom Boston is named.

Tuesday, April 20, 2010

Walking the Post Road

“ As to politeness and humanity, they (the northern provinces of colonial America), they are much alike except in the great towns where the inhabitants are more civilized, especially att Boston”

Dr. Alexander Hamilton, Gentleman’s Progress: The Itinerarium, 1744 (1)

Left: Paramount Theater Boston Theater District, Opened 1932 reopened 2010.

Right: Empire Garden Restaurant, Chinatown. Washington Street between Beach and Kneeland. 1/2 mile from Old State House. Formerly the Cove area.

Left: Seal in pavement with image of Boston Gate, Washington Street near East Berkeley St, South End

Left: Province House Plaque Right: View down Washington Street

near Downtown Crossing

Right: Washington Street at Herald Street overlooking the Massachusetts Turnpike. The desolation as a result of redevelopment and the impact of the highway and railroad tracks act as a gate to the old town just as surely as the original gate on the Neck.

Above: Wayside at the Silver Line station, corner of Washington and East Berkeley Streets. This is the approximate location of the original entrance to the town of Boston. The map shows the original shoreline as well as subsequent development of Boston by reclamation of land submerged in the first two hundred years of colonial life in Boston.

1 Carl Bridenbaugh, Cities in the Wilderness: The First Century of Urban Life in America, 1625-1742 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1938; paperback edition, 1971), 6.

2 Ibid, 6.

3 Ibid., 4.

4 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_towns_and_cities_in_England_by_historical_population

5 US Census, population of 24 Urban places, 1790, http://www.census.gov/population/www/documentation/twps0027/tab02.txt, accessed April 22, 2010

6 http://www.oldsouthmeetinghouse.org/default.aspx

7 see Van Wyck Brooks, The Flowering of the New England Mind (New York: EP Dutton & Co., Inc., 1936; reprint Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1981, for details

8 Walter Muir Whitehill, Boston: A Topographical History, 2d ed. enlarged (Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1968), 104.

9 http://www.census.gov/population/www/documentation/twps0027/tab03.txt

10 http://www.census.gov/population/www/documentation/twps0027/tab08.txt

11 Wayside Washington Street and Herald Street at Silver Line station. Every station shelter has an extremely interesting exhibit about the history of the area around the shelter complete with images and maps.