Entry #23: Mile 51, East Providence. Making Ends Meet.

The Post Road in the area around Providence can be quite confusing. There seem to be roads spinning off in multiple directions, some of which do not seem as though they are getting me any closer to New York. If one digs back in time the present situation becomes a little clearer. The Indians, as I have mentioned previously, took the path of least resistance to get from point A to point B as their only land-based option was to walk. They avoided hills and swamps and crossed rivers at narrow points or where the water was shallow. Pawtucket Falls was the narrowest point in a direct line from Massachusetts Bay to the Narragansett country of southern Rhode Island and thus a crossing was established here. A trail then led into what is now Providence where another crossing, this time of the Providence River, allowed a continuation down the western shore of Narragansett Bay. A second crossing of the Blackstone/Pawtucket/Seekonk River (all the same water, just different names in different sections), at what was called the “narrow passage” of the Seekonk River, presently located at Henderson Bridge, allowed for a boat crossing of about 600 feet, from where the trail crossed over the Eastside of Providence to the Providence River, which was forded as mentioned above.(2)

Travel to Newport, located on an island, also required a ferry crossing. In this case most travelers from Boston followed a trail across the plains east of the Seekonk River in what is now Pawtucket and East Providence. Those traveling to Providence turned west at the “narrow passage” while the Newport bound continued south to another ferry, between what are now the towns of Barrington and Warren in Rhode Island. A second ferry crossing at the tip of the peninsula at Bristol brought travelers to the island of Aquidneck, and a 12 mile jaunt down the island brought them into Newport. Those journeying from Providence to Newport also had the option of crossing at India Ferry as I discussed last time. A bridge crossing the Pawtucket Falls was built in 1713, and travelers to Providence switched from the “narrow passage” crossing back to the Pawtucket crossing.

To summarize, Newport travelers stayed on the east side of the Seekonk River, bypassing Providence, while travelers heading directly to New York went through Providence one way or another, depending on whether the bridge had been built at Pawtucket. The question remains, why bother going to Newport at all if your destination is New York? Well, one reason is that many people journeyed from Newport to New York by boat, which in the eighteenth century was often much easier than traveling by land through Connecticut. Take a look at the map below. Travel by sea from Boston to New York was certainly possible and frequently done, but it required a trip around Cape Cod, which made the trip substantially longer. By going down to Newport or Bristol the traveler could now hop on a boat and travel a much shorter distance to New York.

A second reason many visitors passed through Newport on their way to New York or Connecticut was that Newport, for much of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, was one of the four or five largest towns in the colonies, and any traveler or merchant might have business there as well as in New York. Providence just was not as big as Newport in the colonial period. In 1730 Newport’s population of 2800 made up 40% of the 7000 inhabitants of Rhode Island, and by 1790 Newport’s 6716 inhabitants still comprised almost 10% of the 69,000 people living in the Ocean State, while Providence lagged only slightly by 1790 with a population of 6380, after essentially having only a few hundred in the early eighteenth century. After the Revolution Providence surged while Newport lagged. Thus the seeming oddity of visitors traveling to Newport on their way to New York is simply a question of changed priorities and practicalities. Newport today has a population of 26,500, less than 3% of Rhode Island’s population, while Providence has 175,000 within the city limits, 17% of all the people resident in Rhode Island. (3)

*****

I head for Newport from my Providence touchstone, the Roger Williams National Memorial. My goal is to cross the “narrow passage” over to East Providence. I will then detour slightly north to take in Rumford, the original settlement area on the east side of the Seekonk River and an area through which Knight, Hamilton, and Birket would have passed en route. Birket headed south from here, and Hamilton headed north on his way to Boston. I will head south until I link up with Hamilton again as he made his way from India Point on his return trip, and then I will follow a single path all the way to Newport. Sound confusing? I hope this entry clears up some of the confusion. Follow along and you will see that ultimately all I am doing is going from Providence to Newport, linking all the permutations described above so that I have covered the main routes from Massachusetts into Rhode Island traveled in the colonial period, before turnpikes, railroads, and highways made the trip much shorter and more direct.

*****

Left: Houses on Benefit Street, Eastside Providence. Hamilton or Knight may have passed this way. Right: View south from the Henderson Bridge over the Seekonk River. This is roughly the site of the “narrow passage,” or “Upper Providence Ferry.”

Leaving Roger Williams National Memorial (again!), I head up College Hill one block to Benefit Street. The houses lining the street constitute one of the most spectacular collections of colonial and Federal architecture in America, and one might be forgiven for momentarily thinking it is 1790, until a carpenter’s pickup truck rumbles past, spoiling the reverie. I follow Benefit to Angell Street (the same Angell family of the tavern keeper Hamilton satirized) and follow this street up and over the hill, crossing through the Brown University Campus, on my way to the site of the ferry Sarah Knight would have taken to cross into Providence in 1704. Some local histories claim Indians kept canoes at this spot to cross the river which, at 600 feet across, is the narrowest crossing south of Pawtucket Falls until India Point at the mouth of the river as it empties into Providence Harbor. (4) Crossing Henderson Bridge, I reflect that I have now crossed the three crossing points from Boston to Providence.

As I mentioned, a bridge over Pawtucket Falls was built in 1713. Bridges over the other two crossing points were not built until 1793, when the Central Bridge replaced the Upper Ferry and the India Bridge replaced the Lower Ferry. The Central Bridge was in turn replaced by the Red Bridge and finally by the Henderson Bridge on which I stand as traffic rushes past on the way to points east. As I descend from the bridge onto Massasoit Avenue I am in East Providence, a separate city from Providence, comprised of 50,000 inhabitants, the fifth largest city in Rhode Island. The town has an area of 13.4 square miles, which seems relatively small until I look at the map and see that it is only two miles wide on average and therefore 6 or more miles long, meaning my walk in East Providence alone will be pretty substantial. As it turns out, I will end up walking over eleven miles in East Providence, the longest distance I have covered in any town thus far, including Boston.

How is it that East Providence has such a peculiar shape? It is because it has a peculiar history. For starters, until 1862 this area was part of Massachusetts along with the east side of Pawtucket, when it was “traded” to Rhode Island for the city of Fall River. (5) The entire area along the eastern shore of Narragansett Bay was disputed by the two colonies almost from the time Roger Williams set foot in the area in 1636. Williams’s flight from Boston led him to a spring on the eastern shore of the Seekonk River in what is now East Providence on (what a surprise) Roger Williams Avenue, a mile and a half away from the Henderson Bridge following Massasoit Avenue to North Broadway. All would have been well except that the Plymouth Colony argued that its border extended up to the Seekonk River and that he was unwelcome. Hence his flight in a canoe down the river, crossing over to the Narragansett territory

The map above can be better understood by viewing it in a larger form and zooming in or out. The red line indicates the route I followed for this entry, from Henderson Bridge to the southern boundary of East Providence and Barrington, a total of 11 miles. By zooming out you will see the original extent of Rehoboth, originally part of the Plymouth Colony, which merged with the Massachusetts Bay Colony to form Massachusetts. The green line is meant to illustrate that it is much easier to travel to Newport from Boston by avoiding Providence altogether, which explains why so many travelers bypassed the much smaller Providence in the colonial period. At present all the railroads and interstates bypass Newport completely, a sign of the change in the relative importance of the two towns. By zooming even further out you can see how it would have been much shorter to travel by land to Newport and then take a boat to New York or points in Connecticut.

on the opposite shore at India Point (see last entry), and subsequent settlement in what is now Providence, thus forming what became Rhode Island. The Rhode Island Colony claimed almost from the beginning that its territory extended three miles east of the Seekonk River, which would include today’s Pawtucket, East Providence, Barrington, Warren, and Bristol. In 1643 the Plymouth Colony decided to preempt the argument by settling in what is now called Rumford in East Providence, but was originally known as Seekuncke by the Wampanoags who lived there and was called Rehoboth by the settlers. Rehoboth was huge as the map above shows. Little by little towns broke away as was traditionally done in Massachusetts. First was Attleboro in 1694. Rhode Island persisted in its claim, however, and in 1746 won a partial victory by receiving what became Barrington, Warren, and Bristol from Massachusetts. (6) Hence the irony that Bristol County Massachusetts has not had its county town since the middle of the eighteenth century.

The border skirmish continued after the Revolution, even as towns continued to break away from the original Rehoboth town. The western half of Rehoboth broke away in 1812 forming Seekonk, and in 1828 East Pawtucket broke away from Seekonk. Finally, in 1862, Western Seekonk (the area known as Rumford) and East Pawtucket were ceded to Rhode Island in exchange for Fall River, Massachusetts and the borders were settled for good. Thus a 300 year-old person living on Roger Williams Avenue in 1930 in what is now East Providence would have lived in the towns of Seekuncke, Rehoboth, Rumford, Seekonk, and East Providence, and in both Massachusetts and Rhode Island, without ever leaving the house! For good measure, a chunk of old Barrington was attached to East Providence at the southern end, extending the shape of the city into the elongated town we see today. And that clears that up!

*****

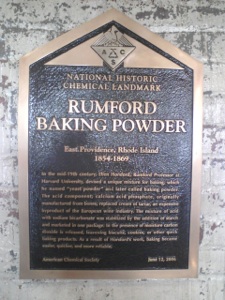

Clockwise from top left: East Providence places of interest. 1. Site of Roger Williams Spring, East Providence, RI. 2. Plaque commemorating the settlement of Seekonk, 1643. Rumford Baking Powder Plaque, in the Seven Sisters Cafe inside the Rumford Building. 4. Newman Congregational Church in Rumford, current version of the original meeting house established in Seekuncke in 1643.

Why do people move? The obvious answer is that they are forced to by various circumstances. In the case of the Puritans, the religious motive predominated, and in the case of Roger Williams, we have the extreme version of that flight, resulting in the establishment of a colony dedicated to separation of church and state. In the case of many others who settled in colonial America, the reasons were predominantly economic. Land was abundant, and the ties that bound people by class were somewhat looser in the colonies. Even after the Revolution, most immigrants arrived for a simple reason, jobs. And jobs aplenty existed in the burgeoning industrial areas of New England.

One such place was the Rumford Baking Company, established in what is now East Providence in 1854. Eben Horsford, Rumford Professor of Chemistry at Harvard, devised a cheaper and easier rising agent by mixing baking soda with an acid salt to produce carbon dioxide. The factory started here on Greenwood Avenue became the largest producer of baking powder in the world in the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century (it was nicknamed “the kitchen capital of America”) and employed so many people that it received its own post office, the Rumford Post Office, which still sits across the street. Alas, the company was purchased and production was moved to Indiana by 1968. The building has recently been redeveloped into offices and has a fantastic bakery cafe called the Seven Stars on the lower floor. The overall feel of the area around Rumford now is one of abandonment followed by nascent efforts at rebuilding the community into something more vital. This cafe is a great step in the right direction. A plaque inside the cafe commemorates the Rumford Baking Company’s role in chemical history, although it looks as though someone made a mistake on the date (1869 versus 1968, see above), which does not give me a whole lot of confidence in the American Chemical Society’s ability to do chemistry!

The original settlement of Seekonk in 1643 was a planned community with home lots doled out around a central common. This peculiar setup became known as the “Ring of the Green,” and Greenwood Avenue marks the southern half of the ring, with Hoyt, Bishop, and Pleasant Avenues completing the circle. (7) Bang in the middle of the Common area, now Newman Street, is the Newman Congregational Church, named for the original pastor. A plaque across the street from the current 19th-century church building is the only indication of the original settlement, as most every building was torched by King Philip’s warriors in 1675. The rebuilt settlement remained small and was engulfed by the factory town that grew up around the Rumford buildings.

The original trail from Boston is diffuse here, as the flat plain of Pawtucket made it unnecessary to travel on a specific path, but Pawtucket Avenue and Broadway are the two roads shown on a map of Rehoboth dated 1795 and most closely correspond to the north-south paths that would have been followed to reach Newport. Both pass through the Ring of the Green. The Vade Mecum of 1732 lists three taverns in Rehoboth. The first, Peck’s, is ten miles from Slacks in Attleboro, which would place it somewhere in what is now Pawtucket, near the East Providence line. This was owned by Joseph Peck (1656-1720) and was called “the Black Horse Tavern.” (8) Five miles further on was Hunt’s Tavern, run by one Daniel Hunt, whose license to run a tavern was renewed in 1724. (9) This tavern, according to the math of the 1732 almanac, would place it somewhere in the Watchemoket area, although Hamilton stopped here in 1744 on his way to Boston and claimed he “ baited at Hunt’s, then (rode) ten miles farther...where I lay that night at one Slake’s att the sign of the White Horse.” (Hamilton, p. 104, July 17, 1744) Somebody is wrong here, but I am inclined to believe the almanac as the math adds up for most of the other taverns.

Both the Peck and the Hunt taverns were involved in a curious story of counterfeiting in the early eighteenth century. In 1723 an interesting court case was heard at Bristol by the Massachusetts Superior Court, Chief Justice Paul Dudley presiding (and so we circle back to the Dudley milestones in Roxbury from my earlier posts). The daughter of Joseph Peck, Mary Butterworth, and Daniel Hunt, proprietor of Hunt’s Tavern, among others, were charged with passing counterfeit money. Ultimately the case was thrown out, but the evidence suggests that Mary was in fact an expert forger and that the taverns were the main place to pass off these false notes to unsuspecting travelers. So good were Mary’s forgeries, according to one source, that many people chose her hand-painted bills over authentic bills! (10) The same source suggests that all of the defendants were connected to prominent families in the town of Rehoboth and that many family members were on the jury that acquitted them of the charges. Apparently the upstanding citizens of Rehoboth used their position on the route from Boston to Newport to their financial advantage and did not want to kill the goose that laid the golden (albeit fools’ gold) egg.

*****

Clockwise from top left: 1. Portugese American Athletic Club, Watchemoket neighborhood of East Providence, an area settled primarily by Portugese and Italian immigrants in the nineteenth century and now home to many new arrivals. 2. Exit from the Washington Bridge over the Seekonk River. In addition to Alexander Hamilton in 1744, George Washington and French Commander Comte de Rochambeau passed this way in 1781 on their way to victory in the American Revolution. 3. Stone marking the Wanamoisett, Watchemoket boundary, now both part of East Providence. 4. Stone pillar marking the East Providence, Barrington boundary. Finally leaving East Providence.

East Providence, Rhode Island is a classic illustration of how things change. The original settlement is almost completely gone, and even the population center of the city shifted in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries as immigrants from the metropolis of Providence poured over the bridges to settle the area south of Rumford, called Watchemoket. So many people came, in fact, that the Town Hall was moved from Rumford to Watchemoket in 1889, and remains in the same area today, on Taunton Avenue, near the Washington Bridge that connects the area to Providence. (11) The area today is not an atypical, slightly faded, urban community. I retrace Hamilton’s steps from the India Point Ferry crossing by heading first down Pawtucket Avenue past golf courses and shopping malls, then down Taunton Avenue to reach the Washington Bridge (named in honor of his passage along this same route in 1781). At this point I turn around and head out away from Providence on Warren Avenue as Hamilton did after crossing the river by ferry. A few yards up the hill from the river I spot a small, nondescript building housing a Korean restaurant called Sun and Moon (no website yet, but the son of the owner is hard at work on one). I hesitate to go in, but I am extremely happy that I did as the exterior gives not the slightest clue that the interior is both well decorated, clean, and inviting. The owner, Jong Lee, is exceptionally friendly, and all I have to say is, that if he recommends something to you, JUST ORDER IT! You will be happy, I assure you.

Extremely satisfied by my superb and surprisingly high quality lunch in an unpromising looking neighborhood, I resume my walk, determined to get through East Providence today. Seven miles down, four to go, but these four turn out to be a lot less interesting than the previous seven. I follow Warren to Broadway and opt to follow the Washington and Rochambeau route through to Barrington, firstly because it is signposted, and secondly, because I already know from scouting out the trip in advance that Route 114, the Wampanoag Trail, the winding road that heads down to Newport slightly to the east, is basically a multilane highway for the next few miles and so impossible to walk along. Eventually I reach Route 103, the Veteran’s Memorial Parkway, which I follow to Willett Avenue, still Route 103 and still Washington and Rochambeau’s route. Along the way I pass a stone marker that indicates I have entered into the area originally known as Wanamoissett, which was attached to Rehoboth in 1747 and became part of East Providence. This neighborhood is now known as Riverside and became well known a century ago as a major amusement park area and vacation spot. All evidence of that is gone today as I pass through nondescript neighborhoods of postwar ranch houses and more modern developments. As the traffic roars past on this busy thoroughfare, I seek some sign of solitude and finally find a small pond, called Willett’s Pond, where two swans gracefully glide along the surface of the water, and I can sit and catch my breath on this very hot day. I sense I am reaching Barrington because I start to smell the ocean, and overhead I see two ospreys engaged in some kind of mating game. Soon I reach a stone marker that indicates the border between Barrington and East Providence.

After over eleven miles, the city of East Providence is past now, and all the various strands of the Post Road to Newport have been connected as I made my way through the various neighborhoods that, pieced together, form the modern city. I have to admit, I never gave East Providence a second thought before this trip, but I feel triumphant that my method of travel has allowed me to see a place with different eyes than the ones that surely would have ignored the scene below had I been driving through on Interstate 195. After all, thousands of other people moved here to make ends meet. From Roger Williams to Eben Horsford to the thousands of Portuguese immigrants to the restaurant owner Jong Lee, they must have seen something they liked or they would have stayed home.

Sunday, August 8, 2010

Walking the Post Road

Rumford Baking Company Building, East Providence, RI

“ On the 16th of September came to my house to board Mrs Elizabeth Herbert... She came from the Island of St. Cristopher.” (1)

Warning out notice submitted by Innkeeper Daniel Hunt September 28, 1734, to the town government, a requirement whenever a stranger came to town. East Providence has seen thousands of strangers come and go over four centuries. Traces of many still remain.

Notes

-

1.Richard LeBaron Bowen, Early Rehoboth: Documented Historical Studies of Families and Events in This Plymouth Colony Township, Volume II (Rehoboth, MA: Privately Printed,1945), 144.

-

2.Edward Field, The State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations at the End of the Century ( Providence: Mason Publishing, 1902), 536-537.

-

3.Richard Mather Bayles, History of Providence County, RI, 2 volumes (New York: Preston, 1891), 48-65, passim.

-

4.Field, 536.

-

5.Joseph Conforti, Our Heritage: A History of East Providence (White Plains, NY: Monarch, 1976), 66-75, passim.

-

6.William G. McLoughlin, Rhode Island: A History (New York: Norton, 1978), 57.

-

7.Bowen, Early Rehoboth, 7-8.

-

8.Ibid., 59.

-

9.Ibid., 93.

-

10. Ibid., 58-84, passim.

-

11. Conforti, 74.